History of the Marengo Collegiate Institute

US Highway 20 runs through Marengo. From the east, it dips down from Coral and runs flat until west of Illinois 23, when the land starts to rise, topping out around West Street. In 1857, this rise was known as “College Hill.” Between West Prairie and Washington Streets, just north of Highway 20, stood a five-story structure of fine, cream-colored West Dundee brick that housed the Marengo Collegiate Institute, providing higher education to “males and females.” Or did it? The lack of evidence of a building on College hill have led some to speculate that the Institute was ever more than a dream.

THE PLAN

The 1850s were a heady time for McHenry County. The Blackhawk war had ended a few short years ago, opening the area to settlement. Towns sprung up across the northern part of the state like mushrooms. Sites that today are almost forgotten – like Greenwood or Chemung – boasted some of the largest populations in McHenry County. Of 18 townships, Marengo ranked number 7 in population with a total of 1,277, according to the U.S. Census. Lewis and Clark had returned from their cross continental excursion only a generation earlier. The Civil War was only a few years in the future, and may have contributed to the ultimate demise of the Institute.

And what would a bustling, financially successful, mighty city of 1,277 inhabitants need more than a College? The Presbyterian Church already ran an Academy in the basement of their church building, started by the founder of the Presbyterian Church in Marengo, Reverend Goodhue. The Marengo Republican-News reported in October 22, 1915 that the Presbyterian Academy had 80 to 120 students in the 1850s. That would mean that almost a tenth of the population of the township was engaged in higher education at just that one institution – and there were others, like Lawrence Academy, in the county. That is a respectful percentage. For comparison, in the 1870s, less than 2 percent of the population attended an institution of higher learning and twenty percent of the adult population was illiterate[1].

The first mention of the Marengo Collegiate Institute in the newspapers is in The Waukegan Weekly Gazette for March 10, 1855, where the charter for the Institute was listed among the acts of the Illinois Legislature. Indeed, in 1855, the Illinois Legislature chartered 13 collegiate institutes, a record[2]. The actual charter was passed February 14, 1855, and provided that the Institute, properly titled “the Marengo Collegiate Institute of the Presbytery of Chicago” was granted the right to admit females and males, and all denominations of Christians[3].

The Chicago Tribune wrote glowingly of the healthy, temperate, Republican, moral, beautiful, well-read “village” of Marengo, ranking Marengo as one of “the more temperate and intelligent communities[4].”

THE FACILITIES

“There is a fine school located here, called the Marengo Collegiate Institute, located under the direction of the Presbytery of Chicago, having a liberal supply of professors and teachers.” Richard Bishop, Postmaster. (Hawes' Illinois State Gazetteer..., 1859)

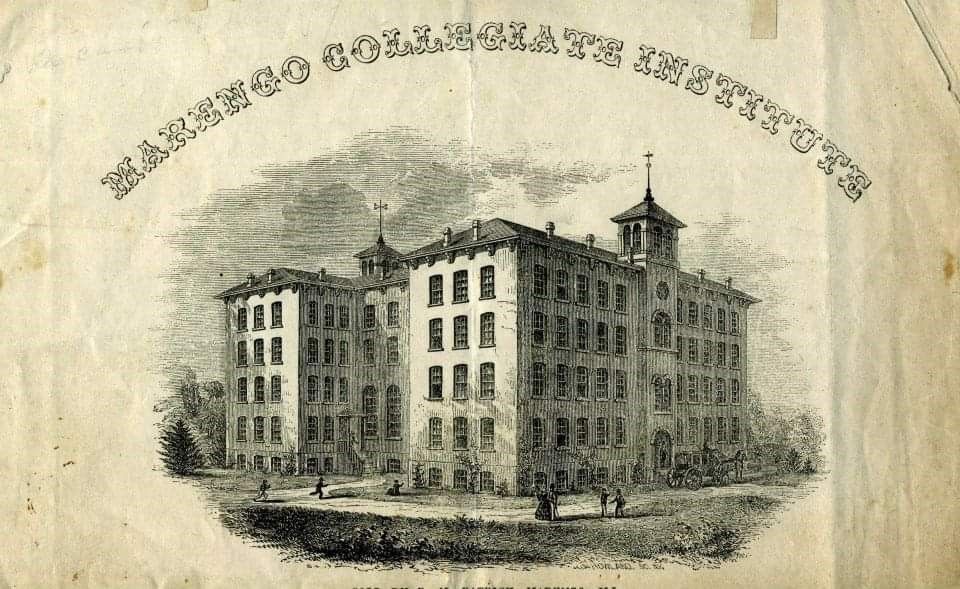

About September 1855, building started on the Marengo Collegiate Institute of the Presbytery of Chicago[5]. On December 13, 1856, the Marengo Journal published an article about the Institute. The article notes “It is not yet finished,” meaning that the building had been started at the time of publication. The building in the engraving looks like a capital “H.” The article notes that “the back wing seen in the engraving has not yet been built,” and notes that the building was shaped like a capital “T.” The article goes on to describe the building as being 5 stories, built of Dundee Brick, with a stone basement. From the engraving, it appears that the basement was a garden basement and was being counted as one of the floors. It says it will have apparatus rooms, recitation rooms and a library, meaning those had perhaps not been built yet. The size of the front part of the building (and the planned rear wing) was 37’ by 93’ and the middle portion under construction was 37’ by 43’. In whole, the building as finished in its “T” shaped configuration had a foot print of 5,032 square feet. Assuming all five floors were the same size, and finished, the “T” shaped building would have had approximately 25,000 square feet at the disposal of the institute.

In almost any account of the Institute, the engraving of the five-story brick, “H” shaped building is included. Where the engraving came from is unknown.

On or about March 10, 1862, just over four years after opening, the Marengo Collegiate Institute building burned to the ground. An eye witness account at the time noted that there was insufficient water to fight the fire with even a bucket brigade, and that one man looted the pantry during the fire.

THE PEOPLE

In order for there to be a College in Marengo, there would have had to have been someone who started it. Because the Institute began in the basement of the Presbyterian Church, and continued there after the Institute burned, it is logical to start with the Presbyterian Church. The 1885 History of McHenry County, reproduced in 1976, lists “George F. Goodhine,” as the founder of the Presbyterian Church in Marengo, having come directly from seminary in Princeton, New Jersey, and “He preached for this people seven years, at the expiration of which time he was elected President of the Collegiate Institute[6].” The same 1885 History of McHenry County lists among the instructors of the Institute, a “Geo. T. Goodhue[7].” A newspaper clipping from an un-named source in the McHenry County Historical Society’s library dated July 3, 1974 lists the Secretary of the Institute as one “George F. Doodhue.” Another clipping in the possession of the Society, dated October 1, 1981, lists the “first regular pastor” of the Presbyterian Church as Rev. G.F. Goodhue, and states that Rev. Goodhue was “interested in furthering Marengo’s educational progress.” An original advertisement for the Institute in possession of the Society lists “Geo. F. Goodhue” as “Secretary Board Trustees.” Probably then, Reverend George Franklin Goodhue was the founder of the College and the Presbyterian Church in Marengo, and “Doodhue,” as well as “Goodhine” are typos. In fact, the “History and genealogy of the Goodhue family: in England and America to the year 1890” lists a George Franklin Goodhue who studied at Princeton and “became a home missionary in Northern Illinois; was founder of several Presbyterian churches in that section, where he labored most devotedly and successfully.[8]” He seems a likely founder of the Presbyterian Church in Marengo, as well as the person who started the Prebyterian Academy. When exactly the Academy itself was started is not known at this time; but when the Presbyterian Academy grew into the “Marengo Collegiate Institute of the Presbytery of Chicago,” the original trustees were Anson Sperry, the second attorney in Marengo, president; William Edwards, Treasurer, R. W. Henry, H. A. Brown, vice president, R. K. Todd, who would later found Todd Seminary for boys in Woodstock, agent, M. White, Reverend George F. Goodhue, secretary, R. G. Thompson, and E. Meyers.

While the building housing the institute changed hands several times in its short life, it was last owned by Rev. Isaac Labagh, an Episcopalian who ran a boarding school at the location[9].

ATTENDANCE

The Marengo newspapers report that the opening ceremony for the Institute took place on September 30, 1857. Despite the Presbyterian Academy boasting at least 80 students while it was still housed in the basement of the Presbyterian Church, only about 40 students reported the day after opening ceremonies to begin studies.

Five months later, in early February 1858, the Marengo Collegiate Institute closed for want of funds. A proposition published in the Marengo Journal notes that there were “1 to 25” students. It was still closed in March[10].

Seven months later, on the first Monday of October, 1859, the Marengo Collegiate Institute reopened, but this time only in liberal arts and not sciences and agriculture as previously advertised.

Reported in the Elgin Gazette on Thursday, August 1860, the building was sold “a few days since” at Sheriff’s sale to “an Episcopalian clergyman from the east, who proposes to establish a first-class Collegiate Institute.” The sale price was $5,775 – less than a third of the original cost to build[11]. The Marengo Journal reported that there were “between twenty and thirty” students in attendance[12], and would be “bound to succeed.”

The Marengo Collegiate Institute of the Chicago Presbytery was renamed the “Marengo Institute” and opened a third time on September 19, 1860. A large advertisement was taken out in the Marengo Journal[13]. The instructors were named as Isaac P. Labagh, Peter L. Labagh (later a member of the “Wayne Rifles”[14]), Charles Woodward, Cynthia L’Hote, Carrie Benedict and Elizabeth C. Sperry[15]. This time, it was as a school for young ladies only, and the building itself was named Euphemia Hall[16], after a Greek martyr who suffered a gruesome fate. There were “20 or 30” pupils, according to contemporaneous newspaper accounts.

CONCLUSION

Beginning August 16, 1856, Anson Perry, as President of the Board of Trustees of the Marengo Collegiate Institute, advertised weekly in the Marengo Journal, asking for those who had promised to financially support the Institute to actually pay what they owed. Money was a problem on this case from the beginning. The Chicago Presbytery had pledged financial support for the Institute, but never delivered. This left the organizers in an embarrassing position. They were charged with raising money to run the school, but instead, had to spend all the money that they had raised on building the school, leaving no money to run it. It seems without question that the building was at least partly built, having been built at the same time and by the same Marengo firm that built the Woodstock courthouse. Some similarities in the engraving and the old Woodstock courthouse are apparent. The building was supposed to have been beautiful and visible for miles. But no matter how beautiful, it could not compensate for the lack of funding.

As an Institute, it operated for only five months. It struggled with attendance, funding, and retention of staff. Many dignitaries were invited to the opening ceremony: not a single one attended. In its third or perhaps fourth iteration it burned to the ground. Record keeping was such that no one bothered to clean up title to the land, and some fifty years later, there were legal proceedings to remove the now defunct Institute from title to the land. Despite all this, there were graduates from the “Marengo Institute,” and attendance at the Institute would be worthy of note in biographies and obituaries for decades to come.

EPILOGUE

Every few years, an evergreen public interest piece runs about the Marengo Collegiate Institute. The McHenry County Historical Society’s file on the Institute are replete with them. They all say basically the same thing . . . that 150 students attended, that it was five stories tall, opened and closed a few times and ultimately burned to the ground. That is in some respects at odds with what the newspapers at the time reported. How could the story have been so wrong? The answer, I believe, is two-fold. First, later newspaper accounts seem to have conflated the claims that the Institute as planned could “accommodate” 150 to 200 students with actual attendance. There is no indication that at any time there were more than 40 students actually attending the institute. Second, prior to the McHenry County Historical Society’s move to digitize the newspapers for Marengo, it would have been an impossible task to read them all for mentions of the Marengo Collegiate Institute. Each time the Institute was written about, then, the same source material, more or less, was recycled and perhaps embellished with oral memories. Now that the newspapers are available for searching, it is possible to discover what contemporaneous accounts of the Institute actually were. It will be exciting to see what other mysteries wait to be uncovered.

[1] https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teacher-resources/statistics-education-america-1860-1950

[2] the Decatur Herald on May 9, 1963, on Page 16

[3] Private Laws of the State of Illinois Passed at the Nineteenth General Assembly, begun and heard at the City of Springfield, January 1, 1855

[4] Chicago Tribune, Tuesday, January 22, 1856, Page 1

[5] The Marengo Journal notes in the October 13, 1857 edition, reporting on the September 30, 1857 opening ceremony, that building had taken place for “about two years.”

[6] History of McHENRY County, 1885 edition as reproduced 1976, page 740.

[7] History of McHenry County, 1995 edition as reproduced 1976, page 298.

[8] https://archive.org/stream/historygenealogy00byugood/historygenealogy00byugood_djvu.txt, accessed November 23, 2023. As further confirmation for what it’s worth, Ancestry.com has a record of George Franklin Goodhue, B. 1821, D. 1865 at only 44 years of age, who lived in Marengo in 1850; no Goodhine or Doodhue were located.

[9] Woodstock Sentinel, Volume 5, Issue 35 Edition 1, dated March 26, 1862, page 3.

[10] The Belvidere Standard, March 9, 1858, Page 2

[11] Marengo Journal, August 11, 1860.

[12] Marengo Journal, September 20, 1860.

[13] Marengo Journal, November 3, 1860, front page

[14] Marengo Journal, May 18, 1861. The Recruitment or volunteer of the instructors of the institute into military service could not have helped the cause of the Institute – neither could the start of the civil war in the spring if 1861. Surely most people’s attentions would have been on other causes than a college – no matter how grand.

[15] Marengo Journal, November 3, 1860, front page

[16] Marengo Sentential September 12, 1860, Page